A few weeks ago, before the monotony of college bogged down my first-year students, we had a brief pre-class chat about Chaos Theory. After lunch, they entered the room and found all the desks askew. The neat rows and columns facing the board were replaced with desks rotated in various directions. Three young men paused before immediately helping to right the room. And all of them commented, “who could leave the room in a state of chaos.” One student, an engineering major, replied that everything at some point, even our classroom, reverts to a state of chaos or entropy—the second law of thermodynamics.

Days before the class, while on a run around my neighborhood, I listened to an episode of Vibe Check, a favorite arts and culture podcast, where the topic of Chaos Theory also came up. The hosts discussed the political climate that this volatile election (and candidate) created. Co-host Saeed Jones tends towards the philosophical in these kinds of discussions, as poets often do. In talking about the emotions and feelings of another chaotic election cycle, he noted that, yes, chaos is about disorder, but also potential for transformation. That chaos can also be the state before a revolution. As I was mid-anxiety spiral, the statement felt revelatory.

Back in the classroom, I shared the more philosophical angle to chaos theory with my students. And now, this theme now seems to come up everywhere. I am working on a geology book all about small changes over millions of years. One page narrates how tectonic plates separating 0.2” a year may split the African continent into two in the future.

In the arts world, young artists are having a particularly hard time navigating an unstable market. Some analysts think this decline represents the consequences of hype and market value driving taste versus excellence, rigor, and skill. Art critic Blake Gopnik crystallized this idea in the image of museums exhibiting million-dollar “big, colorful pieces that look good over a sofa.” So, without effective criteria and standards driving the price of a work, the market can balloon and crash like the housing market did in 08. Gopnik argues this crash can offer a corrective and turn back towards quality over popularity.

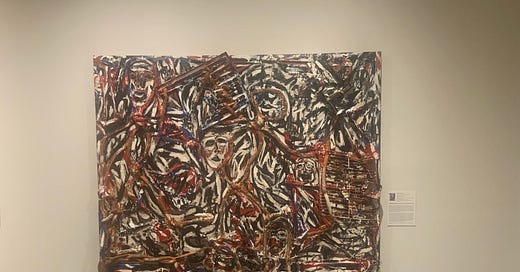

I also think about Black artists whose work does not involve realism, figuration, or representation. To be clear, I don’t consider abstraction, conceptual, or performance work chaotic. Their works push us towards visual or emotional discomfort and bring us somewhere new. My mind immediately goes to JAM, the art gallery and incubator Just Above Midtown. From 1974-1986, founder Linda Goode Bryant worked with Black artists across mediums who did not practice social realism and were often left out of the art world. Bryant did all of this while always on the precipice of closure. Over JAM’s short but impactful time, money, stability, and order would always remain out of reach. A MoMA exhibition in January 2023 that I covered showed the extent of the gallery’s financial difficulties along with their efforts to help Black artists find that stability. And yet, amidst that chaos—a gallery poised to fold at any moment—noted artists like Suzanne Jackson, Lorraine O’Grady, and David Hammons were introduced to the art world.

And yet, my chaotic life does not feel generative yet. I grow more impatient each day waiting for the storm to pass. Family illnesses or deaths disrupted long-held routines, and now those routines have become stale. Despite all the small shifts and big moves that I make, I encounter the same wall over and over again. Or, this could be the last few moments before my evolution becomes visible even to me.