I’m thinking about Beyoncé’s country era, “Ghost in the Machine” by SZA and Phoebe Bridgers, and Brittney Howard’s new album. Middle school Taylor would smile brightly, knowing that genres, activities, or aesthetics don’t have to define or distinguish Black from white people stuff. So much of the art I am engaging with these days purposely blurs genres. The artists I admire search for what feels, sounds, looks, and reads as authentic. Beyoncé grew up in Houston and moded her sound and career after Tina Turner. SZA’s list of influences sounds like my iPod mini on shuffle. Britney Howard screams like Rose Stone in “Sing a Simple Song” and punk bands. At their best, these artists make magic, internalizing influences of all kinds to produce a singular sound, vision, or perspective.

I, too, channeled all of my intersecting influences when crafting my adult and literary selves. My mom’s family grew up working class Brooklyn in the 60s. And they wouldn’t let me forget this fact, even as they sent me to private school with the children of the 1%. This same mom put my sister and me in Jack and Jill. My dad protested this, remembering comments the organization’s mothers made during his childhood about my paternal Grandmother. A nurse who owned her home and raised her son alone with a noticeable Turks and Caicos Islands accent could not become a member. And I couldn’t trust my peers to understand why Evanescence, Paramore, and Fall Out Boy resonated more than most popular R&B or Hip Hop. At the time, genres felt restrictive, like cliques. I resisted only belonging to one group that would dictate how I could move. I wanted these lines between experiences to feel like open doors, not fault lines.

Except porous boundaries don’t spin the wheels of capitalism; they’re more like one-way windows. In the podcast Into It with Sam Saunders, host Sam and scholar Tressie McMillan Cottom discuss how Nashville built a billion-dollar industry by promoting country music as white only. As the music industry formed in the early 20th century, decision-makers split American music split into Hillbilly music for white musicians and Race records for Black musicians using the same banjos that traveled with the enslaved from West Africa. Hillybilly music eventually became country music. Elvis becomes the King of Rock and Roll by watching Big Mama Thorton. And Gwen Stefani’s pop rock sounds and aesthetics transitioned from Riot Grrl ska punk to Valley Girl RnB to the Harajuku Girls era. These markers only restrict Black artists, who are creative sources for most of these genres, from receiving the same credit and money that white artists do.

A moment of genre fluidity I hold onto happened in Questlove’s documentary Summer of Soul. As Questlove explains the context for the 3rd Harlem Cultural Festival, he takes a moment to appreciate the diversity of acts that all shared the same stage: rock, gospel, funk, Motown, psychedelic, and acoustic sets all over three days. Festival organizers celebrated various shades of Black experiences. The closest I got to experiencing this kind of festival was Afropunk in 2012. A battle of the bands and tattoo competition happened on the same weekend as Janelle Monae scream-singing and dancing like James Brown. (Janelle Monae does not scream-sing anymore, and that’s a shame. More Black women should scream-sing.)

Gatekeepers like to say categories help consumers find the things they already like. But labels have only kept me from finding the sounds and sensations that actually matter to me. How would I combine feeling like Rory Gilmore meets Black Daria and As Told by Ginger into one label? What genre encapsulates listening to women scream-sing while looking like I’m ready to conjure new worlds or write a novel? My journey as a writer and arts stan looks like flitting from one obsession to the next, carrying pieces of those communities with me and building work that looks to funnel all these competing and complementary aesthetics into one singular vision.

If you liked this piece, try this one next…

Fandom, Stanning, and Culture

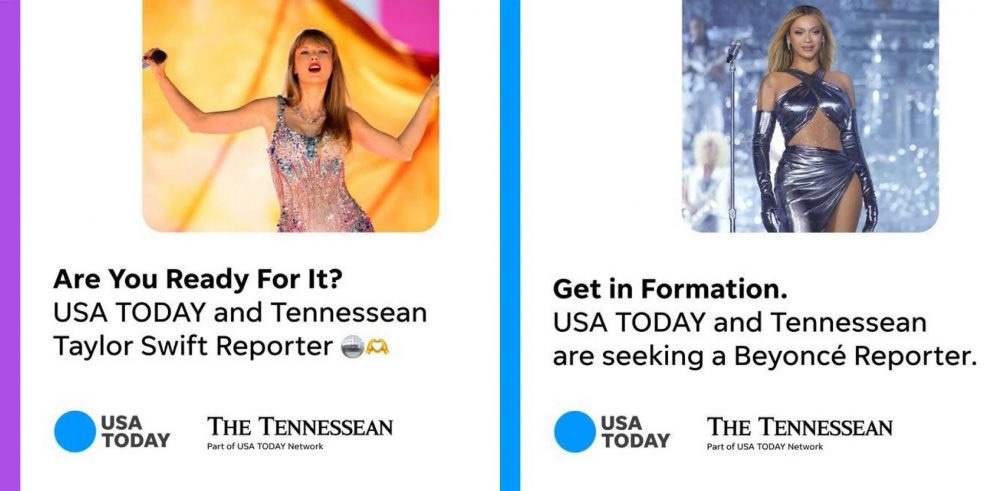

About five days ago, two journalism jobs posted then went viral seemingly within the same click. Through USA Today, Gannet looks to hire a Beyoncé and a Taylor Swift reporter to cover those pop singers exclusively. Each reporter would cover new music and other outputs from the stars and the cult of fandom and influence that both continue to cultivate.

What happens to a suppressed Soul?

Most of my critical interests involve Black arts and entertainment, so calling this month a Black History Month series might seem redundant. But, for Black History Month, I would like to use each post to reflect on significant cultural or historical trends in Black arts and culture. For this post, I analyze how Soul is now doing as a cultural phenomenon…